Hyperion (moon)

|

|

|

Discovery

|

|

|---|---|

| Discovered by | William Bond, George Bond, William Lassell |

| Discovery date | 16 September 1848 |

|

Designations

|

|

| Alternate name(s) | Saturn VII |

| Adjective | Hyperionian |

| Semi-major axis | 1,481,009 km[1] |

| Eccentricity | 0.1230061[2] |

| Orbital period | 21.276 d |

| Inclination | 0.43° (to Saturn's equator)[3][4] |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

|

Physical characteristics

|

|

| Dimensions | 328 km × 260 km × 214 km[5] (geometric mean 263 km) |

| Mean radius | 135.00±4.00 km[6] |

| Mass | 0.5584±0.0068×1019 kg[7] |

| Mean density | 0.5667±0.1025 g/cm3[7] |

| Equatorial surface gravity | 0.017–0.021 m/s2 depending on location[8] |

| Escape velocity | 45–99 m/s depending on location [8]. |

| Rotation period | chaotic |

| Axial tilt | variable |

| Albedo | 0.3[9] |

| Apparent magnitude | 14.1[10] |

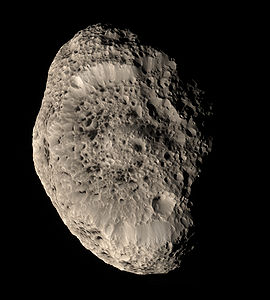

Hyperion (pronounced /haɪˈpɪəriən/,[11] or as in Greek Ὑπερίων), also known as Saturn VII, is a moon of Saturn discovered by William Cranch Bond, George Phillips Bond and William Lassell in 1848. It is distinguished by its irregular shape, its chaotic rotation, and its unexplained sponge-like appearance.

Contents |

Name

The moon is named after Hyperion, the Titan god of watchfulness and observation - the elder brother of Cronus, the Greek equivalent of Saturn - in Greek Mythology. It is also designated Saturn VII. The adjectival form of the name is Hyperionian.

Hyperion's discovery came shortly after John Herschel had suggested names for the seven previously-known satellites of Saturn in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope.[12] William Lassell, who saw Hyperion two days after William Bond, had already endorsed Herschel's naming scheme and suggested the name Hyperion in accordance with it.[13] He also beat Bond to publication.[14]

Physical characteristics

Shape

Hyperion is one of the largest highly irregular (non-spherical) bodies in the solar system (second to Proteus). It has about 15% of the mass of Mimas, the least massive spherical body. The largest crater on Hyperion is approximately 121.57 km in diameter and 10.2 km deep. A possible explanation for the irregular shape is that Hyperion is a fragment of a larger body that was broken by a large impact in the distant past.[15]

Composition

Like most of Saturn's moons, Hyperion's low density indicates that it is composed largely of water ice with only a small amount of rock. It is thought that Hyperion may be similar to a loosely accreted pile of rubble in its physical composition. However, unlike most of Saturn's moons, Hyperion has a low albedo (0.2–0.3), indicating that it is covered by at least a thin layer of dark material. This may be material from Phoebe (which is much darker) that got past Iapetus. Hyperion is redder than Phoebe and closely matches the color of the dark material on Iapetus.

Hyperion has a porosity of about 0.46.[8]

Surface features

Voyager 2 passed through the Saturn system but photographed Hyperion only from a distance. It discerned individual craters and an enormous ridge but was not able to make out the texture of the moon's surface. Early images from the Cassini orbiter suggested an unusual appearance, but it was not until Cassini's sole targeted flyby of Hyperion on 25 September 2005 that the moon's oddness was revealed in full.

Hyperion's surface is covered with deep, sharp-edged craters that give it the appearance of a giant sponge. Dark material fills the bottom of each crater. The reddish substance contains long chains of carbon and hydrogen and appears very similar to material found on other Saturnian satellites, most notably Iapetus.

The latest analyses of data obtained by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during its flybys of Hyperion in 2005 and 2006 show that about 40 percent of the moon is empty space. It was suggested in July 2007 that this porosity allows craters to remain nearly unchanged over the eons. The new analyses also confirmed that Hyperion is composed mostly of water ice with very little rock. "We find that water ice is the main constituent of the surface, but it's dirty water ice," said Dale Cruikshank, a researcher at the NASA Ames Research Center.[16]

Rotation

The Voyager 2 images and subsequent ground based photometry indicate that Hyperion's rotation is chaotic, that is, its axis of rotation wobbles so much that its orientation in space is unpredictable. Hyperion is the only known moon in the solar system that rotates chaotically, but simulations suggest that other irregular satellites may have done so in the past.

It is unique among the large moons in that it is very irregularly shaped, has a fairly eccentric orbit, and is near another large moon, Titan. These factors combine to restrict the set of conditions under which a stable rotation is possible. The 3:4 orbital resonance between Titan and Hyperion may also make a chaotic rotation more likely. The odd rotation probably accounts for the relative uniformity of Hyperion's surface, in contrast to many of Saturn's other moons which have contrasting trailing and leading hemispheres.[17]

Exploration

Hyperion has been imaged several times from moderate distances by the Cassini orbiter. There was one close targeted fly-by, at a distance of 500 kilometres (310 mi) on 26 September 2005. There are no plans for any more.

References

- ↑ Computed from period, using the IAU-MPC NSES µ value

- ↑ Pluto Project pseudo-MPEC for Saturn VII

- ↑ NASA's Solar System Exploration: Saturn: Moons: Hyperion: Facts & Figures

- ↑ MIRA's Field Trips to the Stars Internet Education Program: Saturn

- ↑ Thomas, P.C; Black, G. J.; Nicholson, P. D. (1995). "Hyperion: Rotation, Shape, and Geology from Voyager Images". Icarus 117 (1): 128–148. doi:10.1006/icar.1995.1147. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995Icar..117..128T.

- ↑ "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 13 July 2006. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 R.A. Jacobson et al. (2006). "The Gravity Field of the Saturnian System from Satellite Observations and Spacecraft Tracking Data". Astronomical Journal 132: 2520–2526. doi:10.1086/508812.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 P.C. Thomas et al. (2007). "Hyperion's Sponge-like Appearance". Nature 448 (7149): 50–56. doi:10.1038/nature05779. PMID 17611535.

- ↑ D.R. Williams (18 September 2006). "Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/saturniansatfact.html. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ↑ "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. http://www.oarval.org/ClasSaten.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ In US dictionary transcription, us dict: hī·pēr′·ē·ən.

- ↑ W. Lassell (1848). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 8 (3): 42–43. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/MNRAS/0008//0000042.000.html.

- ↑ W. Lassell (1848). "Discovery of a New Satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 8 (9): 195–197. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/MNRAS/0008//0000195.000.html.

- ↑ W.C. Bond (1848). "Discovery of a new satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 9 (1): 1–2. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/MNRAS/0009//0000001.000.html.

- ↑ R.A.J. Matthews (1992). "The Darkening of Iapetus and the Origin of Hyperion". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 33: 253–258. Bibcode: 1992QJRAS..33..253M.

- ↑ "Key to Giant Space Sponge Revealed". Space.com. http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/070704_sponge_moon.html. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ J. Wisdom, S.J. Peale, F. Mignard (1984). "The chaotic rotation of Hyperion". Icarus 58: 137–152. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(84)90032-0. Bibcode: 1984Icar...58..137W.

External links

- Cassini mission Hyperion page

- Hyperion Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- The Planetary Society: Hyperion

- NASA: Saturn's Hyperion, A Moon With Odd Craters

- Cassini images of Hyperion

- Images of Hyperion at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||